What Is Infrastructural Meaning-Making and Why Do We Need It?

Jutta Haider and Olof Sundin

Social media, search engines, and recommendation systems provide a constant stream of data that shapes our knowledge, beliefs and decisions. We are constantly presented with content from a variety of sources, often without context. This content gets amalgamated into new constellations in the feeds, lists and streams we encounter (and sometime curate) on our devices. With the rise of consumer-facing, generative AI tools, the line between synthetic and other media becomes increasingly blurred. All of this has far-reaching implications for how individual people and society as a whole engage with information and knowledge. But here’s the thing: Not only is it becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish fact from opinion, but also to understand why certain content ends up in our feeds, recommendations or search results in the first place. Yet it’s more important than ever to understand it. This is where infrastructural meaning-making comes into play, and it’s something that the datafied society needs to understand.

—it is crucial to understand how meaning emerges through information infrastructures—

Infrastructural Meaning-Making

Infrastructural meaning-making goes beyond examining the content’s sources, and even beyond evaluating the sources’ content, to also be concerned with the institutions and systems, the platforms and algorithms that deliver it to us and onto our devices. To grasp infrastructural meaning-making, think of a news article you find in your social media feed. Traditionally, we would assess the article against a set of established criteria, such as in the CRAAP test (currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, purpose). More apt for digital environments and non-scholarly literature, we could source and fact check it by following the SIFT model (Stop; Investigate the source; Find better coverage; Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context). This way we (re)contextualize the claims made in the article. And if we understand information literacy as part of our practices we would also consider the social situation in which our encounter with this article is couched.

Content, context, situation—and infrastructures

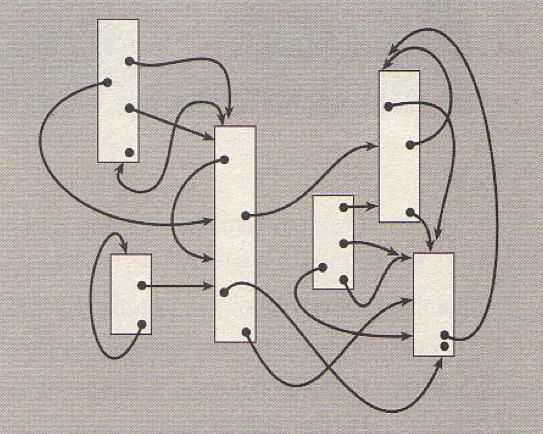

All this is important, but it’s only part of the story. In addition to content (CRAAP), context (SIFT), and situation (information literacy/practices), it is also crucial to understand how meaning emerges through information infrastructures. The information infrastructure plays an important role in determining both what we see and what we do not see, as well as how and when we see it. Therefore, the advice to check your sources is extended to checking how the platforms provided you with your sources in the first place.

In our example, understanding why the news article appeared in our feed at a specific time helps us understand its significance. For instance, it may be due to an advertising campaign targeting our demographic, or it could be because one of our contacts actively shared the article as a “must-read.” But also because a contact engaged in a heated argument with the author through the comments section. This has implications not only for our understanding of the article but also for society, given that a defining characteristic of contemporary information infrastructure is the creation of value and meaning through network effects.

Data fragments brought together

Consider two scenarios for presenting data that many of us have encountered on social media or through a web search engine. First, imagine coming across a graph illustrating temperature trends that suggests talk of a climate crisis is vastly exaggerated. This image is easy to share, and the graph seems to be self-explanatory. However, without a deeper understanding of the context, it’s easy to misinterpret. Often, these graphs omit important details about the origin of the data, or they misrepresent scales in various ways.

Second, here is another illustrative example: comparing recorded sexual offenses, particularly rape, in different countries. You may come across visualizations ranking countries based on these statistics, which makes for attention-grabbing content. Often, Sweden is among the countries with the highest rape rates, while the UAE, where women were not even allowed to drive a car until 2018, has far lower rates. Clearly, there is something off. These lists typically lack important details, such as the legal definitions of sexual offenses, the willingness of victims to report them, whether the data reflects reports of rape or convictions, and similar factors. The data for each country is likely accurate in terms of technical definitions, but the visualization that compares them is not.

In both these case—the representation of climate data and that of rape rates—a deeper understanding emerges when we examine the systems and institutions that lie underneath. How were these statistics collected, categorized, and ordered? Who curates, maintains and shares the data and how? A SIFT approach will remind you to fact-check and source-check the graphs, and quite possibly, if you invest enough time, you will end up refuting them.

Lifting the gaze

Infrastructural meaning-making asks us to look in a different direction and to lift our gaze. It puts the spotlight on the paths these images have taken to reach our screens and devices and it pays attention to the new context and situation they contribute to when combined with other content in our feeds and practices.

Infrastructural meaning-making requires an understanding of the different logics that govern society’s information infrastructure in general and specific systems, services and platforms in particular. That is which types of engagement are encouraged and which are discouraged or prevented, what data forms the basis and which values are likely embedded.

Infrastructural meaning-making asks additional questions

- Past: What is the dominant logic governing the platform or institution?

- Present: Why am I getting this information here and now?

- Future: How do my actions shape my future and that of others?

“That seems difficult,” you might say. And we agree. Most platforms are designed to provide a seamless experience and therefore hide these factors from their end-users. On top of that, today’s digital culture is one of constant connection, where we are literally inundated with content in all kinds of formats. So when is there even time for being that reflective? We cannot spend our lives vetting every dubious piece of information we come across using CRAAP, SIFT, and an information practices perspective, let alone adding infrastructural meaning-making to the mix. We would do little else.

Meaning through constellations: Ignore or explore

First of all, the ability to make decisions about what deserves attention in this way and what should be ignored ought to be part of our information literacy (see also research on critical ignoring). Infrastructural meaning-making can help with that decision. To explain, there is no way to conclusively trace the algorithmic and social path for every post or search result that baffles us. However, if we are familiar with the logic of a particular social media platform, search engine, recommendation service, generative AI tool, or similar—e.g. commercial, extractive, networked, participatory, or democratic—we can lift our gaze far enough to see that meaning emerges differently from different constellations that occur. When we recognize this, we can better decide what to ignore as noise, what to accept, and what needs to be explored in order to be checked.

Does that sound complicated? Yes, it certainly does. But it does not have to be complicated. In fact, infrastructural meaning-making describes something we have found in our research. We have met many people who do just that: they assign meaning to information based on how the platform on which they encounter it functions.To illustrate, people explain how they use someone else’s profile on a streaming service to get different recommendations than they normally would. Others describe how they would strategically use certain search terms foreseeing that those will return results that support or refute an argument. Or it could be the following, as in the case of a young participant in our research. They described that after payday, they often looked at more expensive clothes online because they had the money and noticed that Instagram ended up showing them more high-end fashion ads. But as their finances got tighter, they consciously changed their searches, until their feeds were more about sports.

The people in these examples consider their actions, including their feelings, to be integral to the information infrastructure. The various services they use might be off-the-shelf. But like a collage, the specific combination of services and the constellation of content is unique. More than that, it exists in this form because they have anticipated the likely effects of their actions, thought about it, and acted accordingly.

Many describe doing this intuitively. But some have put a lot of thought into how they act within a given platform, and are very articulate when reflecting on their involvement in the information infrastructure and careful curation of feeds, lists and recommendations. Our contribution is to give it a name that we can use as professionals, educators and researchers in order to make the almost invisible visible: infrastructural meaning-making.

But remember: infrastructural meaning-making is relevant not only to digital but also to analogue and physical information infrastructures. Nevertheless, today we find ourselves in a situation where digital information infrastructures are increasingly submerged, while their control over access to knowledge and meaning is steadily increasing.

If you want to know more about infrastructural meaning-making:

- Haider, J. & Sundin, O. (2022). Paradoxes of Media and Information Literacy: The Crisis of Information. Routledge.

- Haider, J. & Sundin, O. (2019). Invisible Search and Online Search Engines: The Ubiquity of Search in Everyday Life. Routledge.

Cite this article in APA as: Haider, J. & Sundin, O. What is infrastructural meaning-making and why do we need it? (2023, September 21). Information Matters, Vol. 3, Issue 9. https://informationmatters.org/2023/09/what-is-infrastructural-meaning-making-and-why-do-we-need-it/