You Say Robots Have a Race, Ethnicity, or Gender?

You Say Robots Have a Race, Ethnicity, or Gender?

Jessica K. Barfield

Robots equipped with the latest version of artificial intelligence (AI) and that are increasingly humanoid in appearance are coming and not just to our factory floors but to our homes, places we shop and eat, where we receive medical care, and where we go for recreation. They are beginning to serve as our domestic servants and companions, as educators for our children, as financial advisors, and even as behavioral counselors in a time of need. Given the increasing social skills of robots, Communication and Information Science scholars have begun to ask: What factors guide our interactions with robots in social contexts? The answer is, “it depends,” and what it depends on is the design and behavior of the robot and characteristics of the user. It turns out that we don’t treat robots as if they were a collection of mechanical parts and software, simply a tool for human use, but instead we anthropomorphize the robots that we interact with, meaning we assign human characteristics to the robot based on its appearance and behavior.

—how we place robots into social categories not only affects how we interact with robots, but whether we trust robots, and whether we stereotype or discriminate against them—

For example, we might think a robot is being polite if it says “thank you,” or we might think the robot has the personality of an extrovert if it appears outgoing as it communicates with us. And depending on the robot’s physical design and behavior, we may even react to it as if it had a race, ethnicity, or gender. In fact, studies have shown that how we place robots into social categories not only affects how we interact with robots, but whether we trust robots, and whether we stereotype or discriminate against them (Barfield, 2021).

While at first glance it may be surprising that people would categorize robots by a perceived race, ethnicity, or gender, but communication scholars Nass and colleagues (1996, 2007) previously showed that people interact with technology in many ways identical to how people interact socially with each other. To explain this phenomena, Nass and colleagues developed the Computers as Social Actors (CASA) paradigm to describe the way that people mindlessly applied the same social rules used for human interactions with each other to computers. So, in an age of social robots which often resemble people in form and behavior far more than computers, the CASA paradigm seems to apply equally if not more so to robots. It turns out that there are consequences associated with categorizing a robot by a race, ethnicity, or gender which could be positive or negative depending, among others, on whether the robot is viewed as an in-group or out-group member.

While at first glance it may be surprising that people would categorize robots by a perceived race, ethnicity, or gender, but communication scholars Nass and colleagues (1996, 2007) previously showed that people interact with technology in many ways identical to how people interact socially with each other. To explain this phenomena, Nass and colleagues developed the Computers as Social Actors (CASA) paradigm to describe the way that people mindlessly applied the same social rules used for human interactions with each other to computers. So, in an age of social robots which often resemble people in form and behavior far more than computers, the CASA paradigm seems to apply equally if not more so to robots. It turns out that there are consequences associated with categorizing a robot by a race, ethnicity, or gender which could be positive or negative depending, among others, on whether the robot is viewed as an in-group or out-group member.

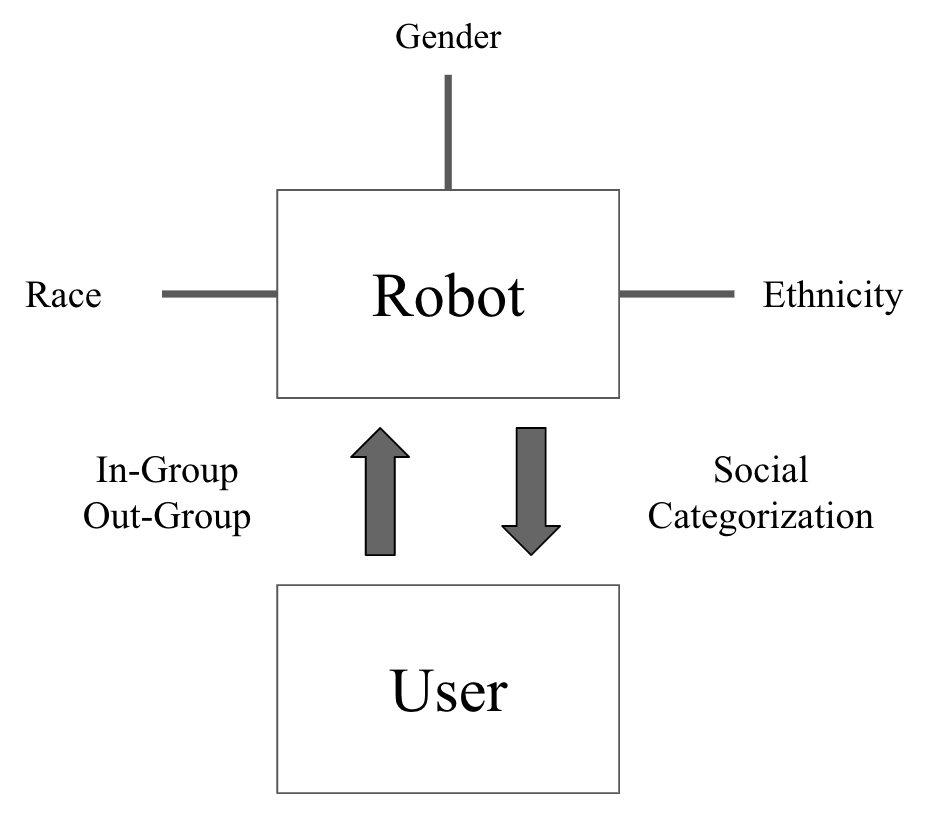

Here I introduce another theory, this time derived from social psychology, which applies to human-robot interaction, and that is Social Identity Theory (SIT). Basically, SIT aims to specify and predict the circumstances under which people think of themselves as individuals or as group members. So, for human-robot interaction, the question is whether we view the robots that we interact with as in-group or out-group members? My research has shown that people are more likely to think of robots as an in-group member if the robot matches their race, ethnicity, or gender (Figure 1).

Once it has been determined that people categorize robots by race, ethnicity, or gender, we can begin to think about how to design robots that accommodate the diverse group of users expected to interact with robots in different social contexts. For example, considering ethnicity, would people from Hispanic or Muslim populations prefer to interact with a robot they felt was similar to their ethnic background? That is, would ethnic cues in the design of a robot that matched those of the user create the impression of diversity, equity, and inclusion in human-robot interaction? Guided by Social Identity Theory and the CASA paradigm, I am currently investigating how social robots are categorized by factors signaling ethnicity, and how robots can be designed to accommodate users with different ethnic identities. I take a user-centered approach in my research in that my interest is to design human-robot interfaces that are inclusive for different user populations as defined by their ethnicity.

In my studies, one issue is how to design robots that project different ethnicities. But how to create a robot thought to have an ethnic identity? I have found that ethnicity can be signaled by several cues, such as behavioral, cultural, socio-economic, and the physical features of the robot’s design. In my studies I vary robot ethnicity in two main ways: by using a spoken accent for the robots that users interact with, and by the content of a narrative spoken to the user. For example, the robot may introduce itself to the user with an ethnic name and indicate a place of origin in say China or Mexico. From my initial studies I have found that minimum cues to ethnicity can trigger the impression that a robot represents that ethnic identity. The next step is to create guidelines for the design of robots that accommodate the different user populations interacting with robots. For human-robot interaction, the one-size-fits-all model in interface design, is not sufficient to create diversity, equity, and inclusion in human-robot interaction, so research on the social categorization of robots holds promise for creating a more just and equitable society.

References

Barfield, J. K., (2023). Designing Social Robots to Accommodate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Human-Robot Interaction, CHIIR ’23: Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Human Information Interaction and Retrieval, 463–466.

Reeves, B., and Nass, C. I., (1996). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places. Center for the Study of Language and Information; Cambridge University Press.

Nass, C. I., and Brave, S., (2007). Wired for Speech: How Voice Activates and Advances the Human-Computer Relationship, MIT Press.

Cite this article in APA as: Barfield, J. K. (2023, May 17). You say robots have a race, ethnicity, or gender? Information Matters, Vol. 3, Issue 5. https://informationmatters.org/2023/05/you-say-robots-have-a-race-ethnicity-or-gender/