Provenance Education to Crack the Cold Cases of Object Origins

Provenance Education to Crack the Cold Cases of Object Origins

Charissa F. Ercolin, Kelley M. Klor, Jane E. Bartley, Lindy K. Baudendistel, Danielle S. Bennett, Sarah A. Buchanan

Tracing the origin and movement of an object is like solving a puzzle that requires design thinking strategies and attention to detail. Like detective work, uncovering the provenance of an object can be a complex endeavor, but one with great reward.

Before diving into those details, we recognize that the word provenance derives from the French verb provenir (meaning to come forth or originate) and is defined as the “history of the ownership of a work of art or an antique” (Oxford English Dictionary, 2022). Many items beyond art and antiques have an origin story too, such as physical and electronic books, buildings, data, and intangible cultural heritage like food or festivities.

The concept of provenance is relevant when purchasing used or second-hand items such as an appliance or transportation device. A buyer may be influenced by such items’ ownership history, maintenance records, and damage or repair trail—datapoints which will only be available if they were remembered and documented, accurately. Similarly, new objects procured for a library, archive, or museum (LAM), must also have reliable records. When metadata are found to be incomplete, unverifiable, or falsified, information professionals require sufficient provenance skillsets and proficiencies to complete the task ethically (Bartley, Buchanan, Reed, Klor, & Ercolin, 2023).

—Clear, complete, and reliable provenance information is crucial for validating an object’s ownership, authenticity, transparency objectives, and value determinations.—

Why does Provenance Matter?

Clear, complete, and reliable provenance information is crucial for validating an object’s ownership, authenticity, transparency objectives, and value determinations.

Ownership: At its core, provenance details an item’s ownership over time to ensure its ethical sale or donation. Supporting documentation, e.g. proofs of sale and international customs forms, legitimizes ownership and can help establish confidence in the accession of an object to a collection.

Authenticity: The provenance of an object serves as evidence towards its authenticity: that it has not been reproduced or altered from its original form. Due diligence involves confirming narratives and documentation—including the unfortunate identification of fake or falsified documents and unverifiable, missing, misinformed, or dishonest narratives.

Transparency: Provenance information helps to answer today’s call for clear and standards-compliant object descriptions. Thorough and explicit information sharing disallows the perpetuation of ambiguities in historical accounts, and advances trustworthy stewardship (Buchanan, Bartley, Bennett, Campbell, Niu, & Reed, 2022).

Value: Once established, provenance can positively impact diverse valuations of objects—from (fair) market to non-market to sentimental to status. A partial dataset of transaction histories for an object of cultural history may, alongside other context resources, assist a repatriation effort.

The Case of the White-Ground Oil Vessel

At The Menil Collection, located in Houston, Texas, a newly digitized sales catalogue provided the missing puzzle piece to determine the origin of a white-ground oil vessel.

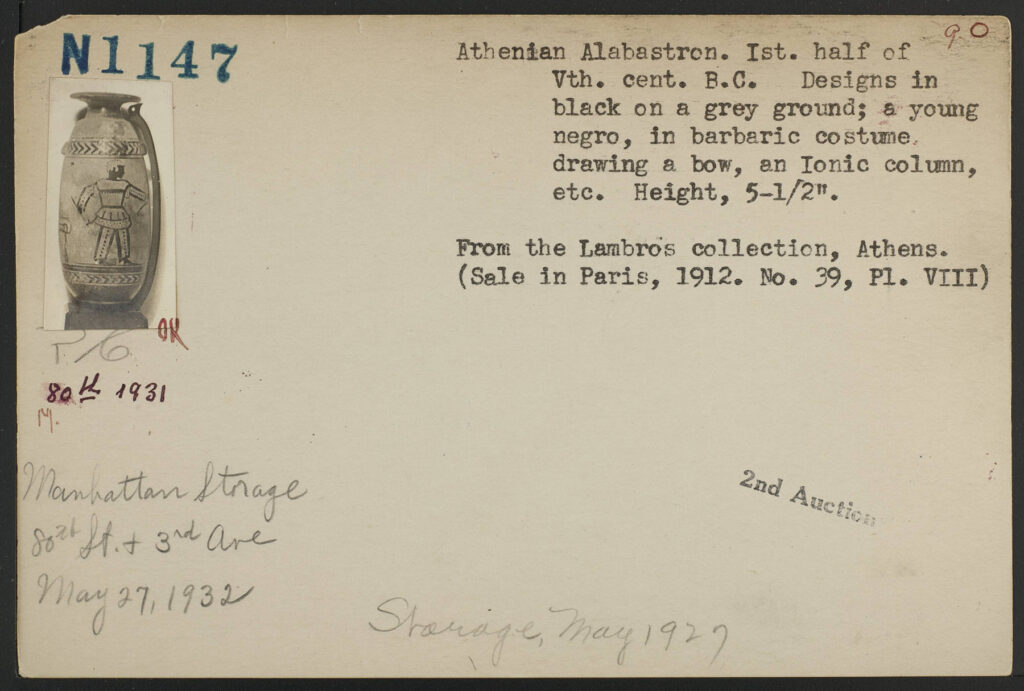

In 1979, the vase was purchased on behalf of the Menil Foundation from the posthumous sale of the Ernest Brummer collection (The Ernest Brummer Collection, 1979: no. 694). The vase can be traced through sales catalogs and digitized dealer archives to have been owned by Ernest Brummer (1895-1964), during the period of 1927 to 1979 (Brummer Gallery Records, 2022: no. N1147).

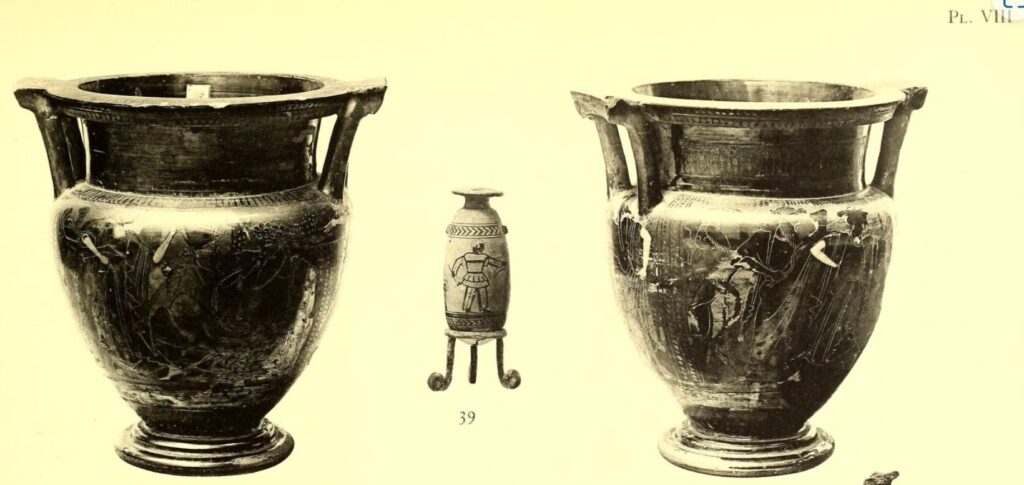

Prior to 1927, the vase belonged to Alphonse Kann, a dealer in Paris, who sold it that year while mentioning a previous “Lambros” collection. The Kann sales catalog clarified that the vase came from the collection of Jean P. Lambros (1843-1909) (Kann & Canessa, 1927: no. 5). Lambros was an archaeologist, collector, and dealer in Athens, Greece whose collection was sold in 1912. The last piece of the puzzle proved to be the illustrated catalog of the 1912 sale (Collections de feu…, 1912: no. 39), which was digitized in 2015.

The 1912 Lambros and Dattari catalog allowed the Menil curators to trace the probable origin of the vase to Attica, Greece. As a result of the provenance research, the vase is now on view as an ethically sourced asset in the Arts of the Ancient World gallery for the first time in its history at the Menil. On account of the renewed interest in the vase, updated photography was completed, which is now available on the collections webpage in order to increase accessibility. As part of its exhibition, the vessel is situated with three other Attic vases, two of which also feature representations of Black African people, on a pedestal with 360-degree access.

Such display allows for dynamic conversations about object histories, production, and subject matter to take place in the gallery. Additionally, the vase and its provenance feature in multiple tours and lectures, including during several class visits from local universities in the 2022-2023 academic year that engaged with the topics of provenance of ancient art and collection histories. During a member event about ongoing provenance research on a different group of objects in the collection, the vase was highlighted as a case study of how provenance research is completed and its significance for understanding the modern biographies of art objects. A short online feature on the vase, its history, and iconography is in progress and there are discussions about updating the website format to include provenance information for all objects in the collection.

Lifelong Learning About Values

Provenance information gathered over time from diverse source materials allows a century-long story of one terracotta vessel to be told—from its time with Lambros (no. 39) to Kann (no. 5) to Brummer (nos. N1147 and 694) to the Menil Collection. Such a provenance-informed story communicates not only the facts of its location and ownerships but even more importantly why it and others are placed in the museum: to deepen people’s educational experiences. With “the principle of provenance, that is ‘the broad administrative and documentary contexts of records creation’ in describing archives, archivists aim ‘to preserve, perpetuate, and authenticate meaning over time so that it is available and comprehensible to all users—present and potential’” (Zhang 2012: 51). People experiencing museum objects learn about them as well as the values of authenticity and information transparency their public display might represent. Digitization allows collaborative work such as provenance research to be more easily completed, which will better contextualize collections thus made accessible. Transparency builds institutional trust that collections have been ethically acquired, and are treated to the highest ethical, legal, and professional standards. Provenance narratives assure visitors that items are genuinely presented in dialogue.

This work extends a case first presented in a poster at the 85th Annual Meeting of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 2022, and is made possible by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, IMLS grant RE-246339-OLS-20.

References

- Bartley, J.E., Buchanan, S.A., Reed, V.S., Klor, K.M., & Ercolin, C.F. (2023). Accessing continuing education for provenance research. In J.G. King (Ed.), 16th Annual Society of American Archivists (SAA) Research Forum Proceedings. Chicago, IL: SAA. Retrieved from https://www2.archivists.org/am2022/research-forum-2022/agenda#peer

- Brummer Gallery Records. (2022). N1147. The Met Cloisters. Retrieved from https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/60597/

- Buchanan, S., Bartley, J., Bennett, D., Campbell, E., Niu, J. & Reed, V. (2022). Examining transparency, due diligence, and digital inclusion as resilient values for provenance research work. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 59: 624-626. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.670

- Collections de feu M. Jean P. Lambros d’Athene et de M. Giovani Dattari du Caire. [1912]. Auction 17th-19th June 1912 at Hotel Drouot, Paris. No. 39 (pl. VIII). Retrieved from p8 and p90 of https://archive.org/details/collectionsdefeu00htel/

- Kann, A. & Canessa, E. (1927). The Alphonse Kann collection, Sold by his order. Vol. 1, No. 5. New York: American Art Association.

- Oxford English Dictionary. (2022). Provenance. In OED Online. Retrieved from https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/153408

- The Ernest Brummer Collection. (1979). Auction sale 16th-19th October 1979 at Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich. Vol. II, No. 694 (pp. 330-331). Zurich: Galerie Koller and Spink & Son.

- Zhang, J. (2012). Archival representation in the digital age. Journal of Archival Organization, 10: 45-68. http://doi.org/10.1080/15332748.2012.677671

Cite this article in APA as: Ercolin, C. F., Klor, K. M., Bartley, J. E., Baudendistel, L. K., Bennett, D. S., & Buchanan, S. A. (2023, June 2). Provenance education to crack the cold cases of object origins. Information Matters, Vol. 3, Issue 6. https://informationmatters.org/2023/05/provenance-education-to-crack-the-cold-cases-of-object-origins/

Authors

-

-

-

Jane Bartley is an MLIS student at University of Missouri and a User Experience Librarian at Virginia Military Institute.

View all posts -

-

Dr. Danielle Smotherman Bennett is Curatorial Associate at the Menil Collection (Houston, TX) responsible for the research and care of the ancient Mediterranean art at the museum. She earned her PhD in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology at Bryn Mawr College, has extensive museum experience in the United States and Greece, and has done fieldwork in Greece, Italy, Turkey, and England.

View all posts -

Sarah Buchanan, ADM, is active in the Association for Information Science & Technology (ASIS&T), having recently served as SIG Cabinet Director in 2018-19 and then on the New Leaders Award Committee. She is an Associate Professor at the University of Missouri’s School of Information Science and Learning Technologies (iSchool), where she serves as the emphasis leader for Archival Studies.

View all posts