Mental Health and Title IX: Challenging Privacy and Transparency

Mental Health and Title IX: Challenging Privacy and Transparency

Madelyn Sanfilippo and Shriya Srikanth

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (hereafter Title IX) plays a prominent role in recent events at US universities. From the University of Michigan firing its president for misconduct to a series of controversies at Harvard University surrounding responses to allegations of sexual harassment against a professor, questions arise about accountability, transparency, and privacy. How transparent are universities about mental health resources and student privacy relative to Title IX? What are best practices for information dissemination relative to these resources? What should students know about privacy, transparency, and mental health relative to Title IX?

Title IX established that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Beyond equal athletic and extracurricular opportunities for women, Title IX provides accountability around sexual misconduct.

—What should students know about privacy, transparency, and mental health relative to Title IX?—

However, Title IX resources and rights are often inaccessible and non-transparent. Information spreads across multiple offices and websites, confusing students who need support. Rather than trusting Title IX offices, students view them as vehicles for compliance and university risk mitigation. Recent events show university priorities are often at odds with students and common assumptions about confidentiality are flawed. Student mental health records are subject to scrutiny in Title IX investigations when they are held by other university departments, including student health or counseling centers.

Privacy, confidentiality, and Title IX

Privacy is the appropriate flow or sharing of personal information relative to contextual norms (Nissenbaum, 2009). Confidentiality is not a complete information flow, but rather a condition of some information flows; privacy is much broader than confidentiality. Confidentiality prevents re-dissemination or private information, such as with doctor-patient or lawyer-client communication.

Privacy and confidentiality are critical to Title IX, yet the law provides little guidance on how to protect information, leaving it to universities’ discretion. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) further complicate university student privacy in the context of therapy, counseling, and student health records. These regulations all intersect, yet fail to directly address the issues at hand and people do not understood them (e.g., Bodie, 2022).

Under HIPAA, sharing psychotherapy notes requires prior approval (DeYoung, et al, 2010), embedding confidentiality and consent in information sharing. Yet, coupled with recent US Department of Education changes about Title IX reporting and cross-examination, privacy expectations about therapist/client confidentially are readily undermined. On the subject of these Trump administration era changes, Senator Patty Murray (WA-D) stated:

Let me be clear: this rule is not about ‘restoring balance,’ this is about silencing survivors… This rule will make it that much harder for a student to report an incident of sexual assault or harassment—and that much easier for a school to sweep it under the rug. There is an epidemic of sexual assault in schools—that’s not up for debate. But instead of responsibly working with advocates, survivors, students, K-12 schools, and colleges to address the issue, Secretary DeVos and this Administration are going out of their way to make schools less safe.

Transparency and Title IX

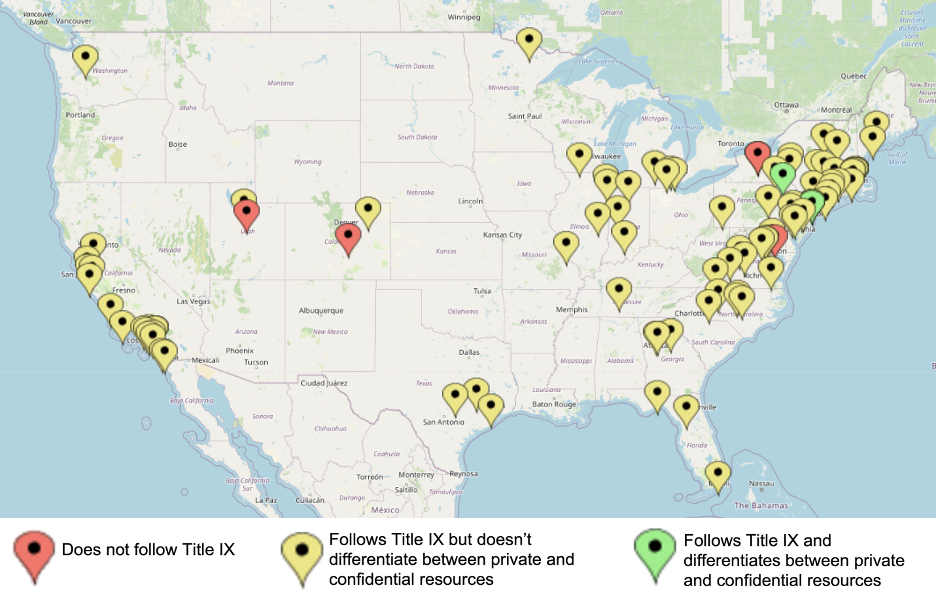

Title IX offices lack transparency around information practices. Content analysis of 100 US universities’ Title IX websites on Forbes America’s Top Colleges List shows most universities do not differentiate between private and confidential resources. Title IX offices do not document how counseling or other support services may be used through investigations. Most websites point students to campus counseling or generic off-campus helplines, without guidance about the implications of those choices. Two notable exceptions include Dartmouth University and Yale University. They provide significant transparency and clearly differentiate between what sources are or are not fully confidential.

Some religious institutions do not receive public funding and are not obligated to comply with Title IX. They do not provide equivalent resources or guidance on the implications of information sharing relative to counseling or therapy surrounding incidents of sexual violence.

Recent Controversies

Recent news stories show governance gaps between students’ expectations about sensitive, confidential therapy and health records and actual protections. In addition, a history of mishandling of misconduct at places like Duke University raises questions about transparency and Title IX efficacy and compliance. Media attention also questions the barriers to information sharing about perpetrators across institutions leading to repeat offenders finding employment at other institutions.

Riding this wave of outrage, associated with recent scandals, a new wave of activism amasses growing support for more transparent communication, more respectful and trauma-informed practices, and resources reflecting diversity of privacy-protection and implications for students. While not everyone agrees on the best path forward, change is necessary and alternatives may be preferable to national consensus. Local communities pursue different paths, reflecting privacy localism in practice, beyond policy. These events often precipitate local action to improve outcomes and practices, such as efforts by 5 women who have channeled their trauma and frustration with Title IX into recommendations at the University of Washington.

Student privacy and Title IX challenges are not merely legal, but also informational and multifaceted. Information scholars and professionals need to play a role in information practices around Title IX.

Recommendations

Universities need to prioritize clarity about the implications of choices and resources for students. Students need to know:

- Faculty and staff, including counselors, are mandatory reporters, meaning they must report sexual misconduct;

- They should ask for clarity about confidentiality before meeting with student health clinic psychiatrists; and

- External resources are trustworthy because they are not compelled to share information with the University.

Further, Title IX Offices should consider adopting the Dartmouth model; as a baseline expectation, all universities should make the distinction between confidential and non-confidential private resources clear to students. Transparency needs to guide conversations about the process, privacy, and resources available to students.

References

Bodie, M. T. (2022). HIPPA. Cardozo Law Review, forthcoming.

DeYoung, H., Garg, D., Jia, L., Kaynar, D., & Datta, A. (2010, October). Experiences in the logical specification of the HIPAA and GLBA privacy laws. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual ACM Workshop on Privacy in the Electronic Society (pp. 73-82).

Nissenbaum, H. (2009). Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of Social Life. Stanford University Press.

Cite this article in APA as: Sanfilippo, M. & Srikanth, S. (2022, May 10). Mental health and title IX: Challenging privacy and transparency. Information Matters, Vol. 2, Issue 5. https://informationmatters.org/2022/05/mental-health-and-title-ix-challenging-privacy-and-transparency/