Stepping Up to BAT: Inspiration for a Research Process Model

Stepping Up to BAT: Inspiration for a Research Process Model

Valerie Nesset

Before you ever entered an information science (IS) program where we are obsessed with all things information, did you ever wonder about how and where you learned to locate, select, and use information – in other words, “do research”? Of course you didn’t! Like me, probably starting in high school, you learned by trial and error what worked and what didn’t. Yet, wouldn’t it be great that at the same time you were learning to read chapter books and basic informational texts, you could learn a research process that could carry you right through post-secondary studies? As M. E. Marland, a member of the UK Schools Council, asserted in 1981, from elementary school to PhD studies, in research, the questions and processes remain fundamentally the same. To find out if that was true for the Canadian context, for my PhD dissertation study I decided to observe the information behaviours of grade-three students as they worked on a class project.

—did you ever wonder about how and where you learned to locate, select, and use information—in other words, “do research”?—

For four months in early 2006 I worked with a teacher in a grade-three class in an English elementary school in a suburb of Montreal, Quebec. What I thought would be a six-week data collection phase turned into over four months! The reason why was revealed in our first planning meeting. I found out that despite engaging in a project-based learning approach, work on a physical project was not going to form the centre of the teacher’s instruction but instead was but one of several methods she would use to assess the students’ learning. In truth, she didn’t see it as overly important to achieving her learning objectives. What she prioritized was the broader topic or “theme unit” (in this case, “Canadian Animals in Winter”) to provide the content for her learning activities. Furthering this premise, she explained that before work on the project could even begin, she needed to “prepare” the students so that they would be ready to actively engage with the content and to begin their physical projects. Upon  hearing this, I started to think about all those information behavioural models I had researched as part of my literature review. Which one of them included a “preparation” stage? They all just seemed to assume that users could read and write at an appropriate level. And what about information retrieval (IR), the “searching for information” phase? In all the models I had researched, this was the stage that garnered the most attention. Imagine my astonishment when I found out that in the teacher’s mind, this phase didn’t exist. She typically prepared information packets for each student to use because she didn’t want to overwhelm them with information too complex for them to understand. When I explained that this phase constituted the crux of my research, although skeptical, she agreed to allow the students to search for information using print sources from the tiny school library collection, and during their 45-minute twice-weekly computer sessions they could search the Web.

hearing this, I started to think about all those information behavioural models I had researched as part of my literature review. Which one of them included a “preparation” stage? They all just seemed to assume that users could read and write at an appropriate level. And what about information retrieval (IR), the “searching for information” phase? In all the models I had researched, this was the stage that garnered the most attention. Imagine my astonishment when I found out that in the teacher’s mind, this phase didn’t exist. She typically prepared information packets for each student to use because she didn’t want to overwhelm them with information too complex for them to understand. When I explained that this phase constituted the crux of my research, although skeptical, she agreed to allow the students to search for information using print sources from the tiny school library collection, and during their 45-minute twice-weekly computer sessions they could search the Web.

While it was apparent that the teacher used content as the means to teach her students, once we started the in-class instruction, I was pleased to see that several of the techniques she used would also serve as preparation for the IR stage. For example, she introduced new terminology related to the theme to further reading comprehension – I could see it being used to enable the more effective construction of search queries for web searching. She read aloud from both fictional and informational texts to demonstrate different kinds of reading – this would also inform the students on the differences between reading for pleasure and reading informational texts to satisfy a query. Her use of what she called “webbing” to present new concepts was, in fact, a simplified concept map which could be used to demonstrate relationships and facilitate the evaluation of retrieved information for relevance. First revelation – many educational activities require minimal modifications to integrate them into a process.

Once the students began searching for information for their projects, it was interesting to observe their decision-making. For example, they did not consider images on their own as “information” because they associated information only with text, but they relied heavily on them as signposts to indicate where to locate informational texts, for instance when searching a book by flipping through the pages. When web searching using simple search queries, images were used for evaluation – a retrieved website was deemed more relevant if it contained an associated image. Second revelation – images and their placement are important.

While searching, the students took short notes, but, given their limited writing abilities and the short time frame, pertinent webpages or book excerpts were printed out or photocopied. Transferring what the students had found in books and the Web into printed sheets also allowed them to spend more time with the information. This enabled more time to reread and reflect on the information so that they could more critically evaluate and analyze it. Third revelation – print is important in a young student’s world and even if they are a “digital native” doesn’t mean everything has to be presented to them on a device.

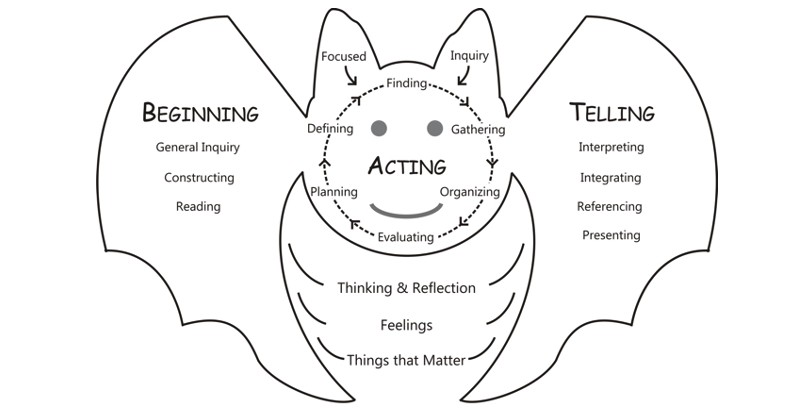

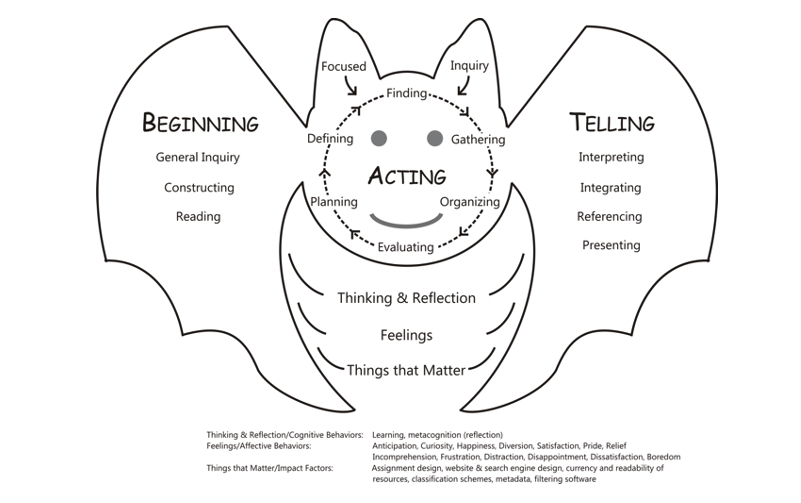

So, where did all this lead me? Well, I used those three revelations as inspiration to develop a visual research process (information literacy) model, Beginning, Acting, Telling (BAT) (Figure 1). Unlike most information literacy models that are textual, outlining a series of steps, since images are important for young students, the BAT model is visual. It uses a stylized image of a bat to present the entire research process (and yes, there is a preparation stage) to allow for recognition, reducing cognitive load. The model also makes explicit more abstract constructs such as things that can affect the research process: thoughts and reflection (cognition and metacognition), feelings (affective behaviours), and external factors beyond the student’s control (things that matter). Currently, I am in the process of bringing the BAT model alive – transitioning it from a static image to an interactive site on the Web which will showcase the “batty way to research.” Stay tuned!

Figure 1: The Beginning, Acting, Telling (BAT) model

Cite this article in APA as: Nesset, V. Stepping up to BAT: Inspiration for a research process model. (2025, April 30). https://informationmatters.org/2025/04/stepping-up-to-bat-inspiration-for-a-research-process-model/

Author

-

Dr. Valerie (Val) Nesset retired from her position as an Associate Professor in the Department of Information Science at the University at Buffalo. Currently, she works as an Information Science consultant at her family business, NesseTech Consulting Services Inc., located in Thunder Bay, ON, Canada.

View all posts