Information Access’s Changing Models from the Library of Alexandria to Google

Information Access’s Changing Models from the Library of Alexandria to Google

Chirag Shah, University of Washington

Throughout the history of humankind, access to information has been treated as public good. It is only in recent history that such an essential service has been commercialized. How did it come to be? Many of us grew up knowing nothing but just this model, but could there be alternatives? Let’s look at other models in history and think about how and why we transitioned from public access to commercialization of information.

Between the shores of the Mediterranean and the Nile River delta, around 300 B.C., the Ptolomeic rulers of the great city of Alexandria began a mission to collect all of the world’s manuscripts. Through payment and plunder, the collection of the Library of Alexandria grew to an estimated 400,000 – 700,000 scrolls, representing the totality of Western knowledge at the time.

But simply creating a big library in a big city was not enough to create the impact Ptolemaic kings wanted from an institution of public knowledge. They knew that before information can be stored and disseminated, that information had to first flow into the library. How do you make that happen? First, of course, you need funds. The Library of Alexandria was well-funded through the state. In fact, the library was also called a Museum—a shrine to the Muses, called a Mouseion in Greek and a Museum in Latin. What it means is this institution was religious in nature, under the watchful eyes of the gods and helmed by a priest. This gave the library the highest honor and recognition possible. The state (the kings) provided all the resources needed not only to the priest (the director of the library), but also to the scholars housed there.

Second, you need experts to obtain and curate information. Per text written in a 2nd Century BC,

Demetrius of Phalerum, the president of the King’s library, received vast sums of money for the purpose of collecting together, as far as he possibly could, all the books in the world. By means of purchase and transcription, he carried out, to the best of his ability, the purpose of the king.

He was asked, ‘How many thousands of books are there in the library?’

And he replied: ‘More than two hundred thousand, O king, and I shall make an endeavor in the immediate future to gather together the remainder also, so that the total of five hundred thousand may be reached.’

How did they achieve this goal? They sent scholars to far away places in the world to seek out any books or scrolls they could find. They bought as many of them as possible, and borrowed the rest to make their copies. As the legend goes, Ptolemy III paid 500 kg of gold to borrow original manuscripts by Sophocles, Aeschylus and Euripides from Athenians.

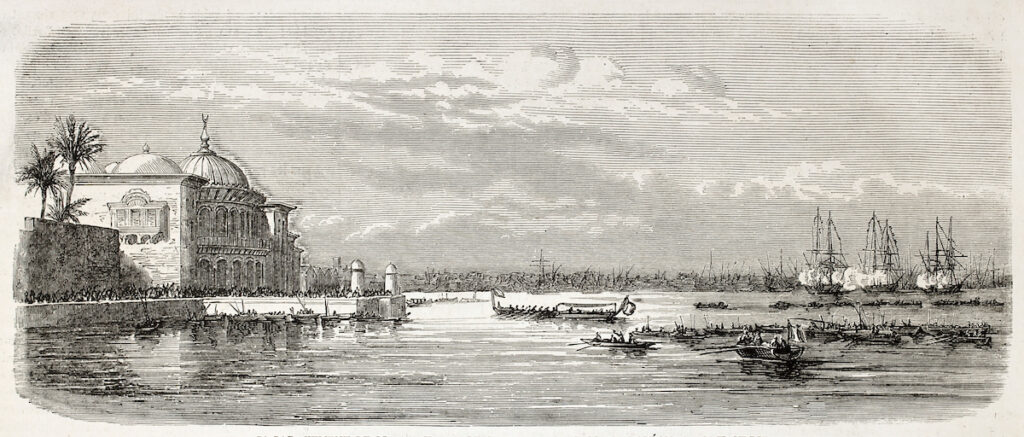

In addition, every ship entering Alexandria harbor was searched for books or other written materials. These items were either purchased or brought to the library to make copies. The scholars there did such a great job with those copies that people couldn’t often tell what was returned to them was the original or its copy. In order to establish Alexandria as a compelling and wealthy port of business for those ships to come in, the Ptolemaic rulers built the Lighthouse of Alexandria, which was considered to be one of the seven wonders of the Ancient world.

The Library of Alexandria wanted to be the beacon of knowledge in the world by ensuring every book in the world was found there for all those who seek knowledge. While funded by a non-secular state, the library was philosophy and religious neutral. It welcomed ideas, texts, and people from any creed or culture. People traveled from long distances to this place to access information and gain knowledge in every possible area imaginable. There was no charge to use the library’s resources. In fact, the scholars who stayed there were provided free food, lodging, and even stipend.

That certainly paid off—not just for the Ptolemaic kingdoms, but for the world. For example, it is said that the famous scholar Archimedes came up with the idea of Archimedes screw while working at the library. This innovation is still in use today. Also here, Eratosthenes of Cyrene first calculated the circumference of the earth. Other famous scholars who did their innovative works here were Aristarchus of Samos and Euclid, the “father of geometry”.

—While we can't go back to the Library of Alexandria, can we envision a better model of information access than "free" and problematic search engines we have?—

There are certainly benefits of a state investing in accumulation, curation, and dissemination of information. On the flip side, there are also challenges with this model.

Many believe that Julius Caesar destroyed The Library of Alexandria. That is not completely correct. Yes, Caesar burned the ships in the harbor and that fire spread to the city, affecting the library. However, the library’s real decline happened through the decline of the Ptolemaic dynasty and Egypt itself. As the Ptolemaic reign weakened and the Roman empire grew stronger, the library’s funding declined substantially. This led to reduction in existing scrolls as well as ingestion of new scrolls. The funding for research and supporting scholars and visitors also dried out. In the end, the buildings may have been destroyed from wars, but the real destruction of the library had begun long ago. And there in lies one of the dangers of state-funded knowledge institutions—they can come and go with the political tides.

An alternative is privately funded model of information storage and access. Of course, this we know quite well. With the proliferation of digital information on the web, we needed tools to catalogue, index, and present information in ways that was scalable and widely accessible. I will skip the history lesson here and jump to the evolution of search engines. And even skip the early era of Lycos and Yahoo to talk about Google, of course. It’s a very useful, very powerful, and very omnipresent system. More importantly, it is running on a very different model—privately funded, free to all to use. Of course, it’s not really free and I have written about it before. What is important here for us is to think about pros and cons of this model compared to the Library of Alexandria.

In a capitalized free-market society, chances are this system is not going to easily disappear. It is also set up as a “free service” like the Library of Alexandria, but not dependent on any state funds or politics to keep it going. It’s built on our collective will and need. It’s almost poetically beautiful—it will exist because we need it to exist. As long as we keep using it, Google will keep getting stream of ad dollars and that can have it keep running.

So what’s the flip side? The Library of Alexandria and for that matter, even modern libraries, are built on a model of curation—managed and provided by qualified experts who consider issues of fairness, transparency and other societal values while preserving and presenting information. Google bears no such responsibility by its design. Sure, it can enforce some guardrails in its algorithms and data curation, but by design, it is a reflection of what our society is (or has been) rather than what it should be or what it needs to be. And that’s a big problem because it creates a very potent cycle where we feed our issues into Google and Google keeps giving us that biased view of the world. It is giving us what we want and what we want is not always the right thing for the greater good. Suddenly, there is no easy enemy like Julius Caesar or Ptolemic kings to blame. And for time being, it seems we are stuck with this model. While we can’t go back to the Library of Alexandria, can we envision a better model of information access than “free” and problematic search engines we have? After all, for most of our history, information access has been considered a public good rather than a service that is profit driven, ad supported, and giving people what they want even if that creates disparities, disfranchisement, and desolation of democracy.

Cite this article in APA as: Shah, C. (2022, September 30). Information access’s changing models from the Library of Alexandria to Google. Information Matters, Vol. 2, Issue 9. https://informationmatters.org/2022/09/information-accesss-changing-models-from-the-library-of-congress-to-google/

Author

-

Dr. Chirag Shah is a Professor in Information School, an Adjunct Professor in Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, and an Adjunct Professor in Human Centered Design & Engineering (HCDE) at University of Washington (UW). He is the Founding Director of InfoSeeking Lab and the Founding Co-Director of RAISE, a Center for Responsible AI. He is also the Founding Editor-in-Chief of Information Matters. His research revolves around intelligent systems. On one hand, he is trying to make search and recommendation systems smart, proactive, and integrated. On the other hand, he is investigating how such systems can be made fair, transparent, and ethical. The former area is Search/Recommendation and the latter falls under Responsible AI. They both create interesting synergy, resulting in Human-Centered ML/AI.

View all posts